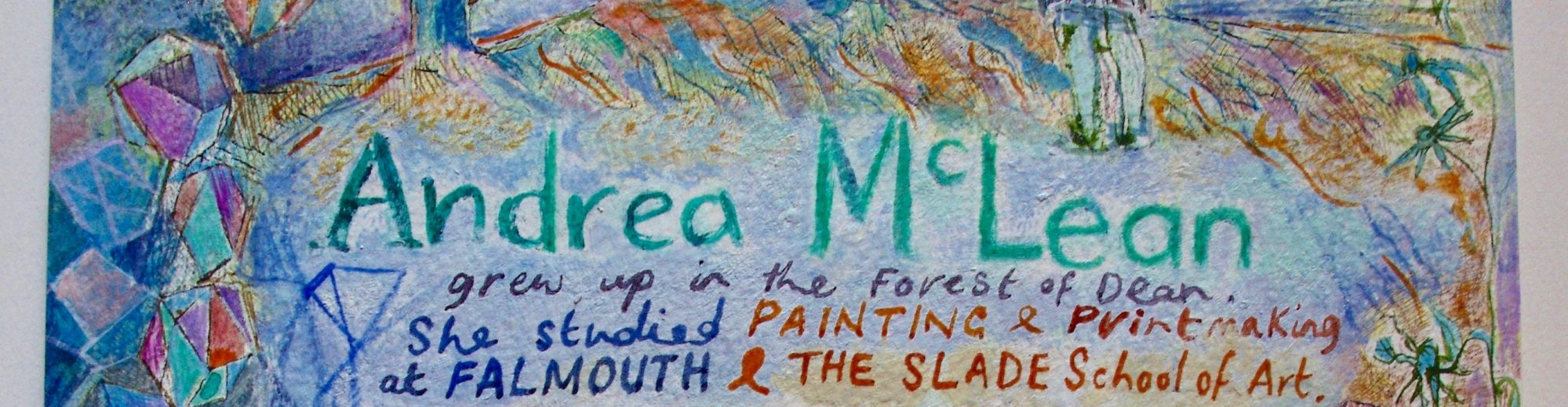

It can happen – very rarely – that an artist paints a single painting that remains with you over the years. Andrea McLean’s Bear is such a picture. She started it while a student at the Slade, and I walked past it several days a week throughout her time there, through all its changing forms and colours. It changed – was changed – continuously over that time, and I didn’t see it finally completed, so can’t know how it ended up, although I believe it still hangs somewhere rather remote.

It can happen – very rarely – that an artist paints a single painting that remains with you over the years. Andrea McLean’s Bear is such a picture. She started it while a student at the Slade, and I walked past it several days a week throughout her time there, through all its changing forms and colours. It changed – was changed – continuously over that time, and I didn’t see it finally completed, so can’t know how it ended up, although I believe it still hangs somewhere rather remote.

This was a painting I wanted to get into, a world that I wanted to enter. The surface is teeming with all the shapes and forms and suggestions of things that suggest another world. It takes a little time to enter it – looking can sometimes be quite hard work. It makes me ask the question, how close is it possible to get into any painting? And reminds me also of that rather charming proposition by Wittgenstein that ‘…the world is everything that is the case’. In Andrea’s work this is explained. Everything here is the case. Because the way it’s painted and drawn and scratched, lightly, delicately, convinces you, yes, this is the case. Every one of these myriad marks has emerged, grown, from somewhere elemental in this artist. I don’t know if these events – birds and beasts, trees, flowers, suns, things within things, were a struggle for her to reach, or if they came teeming from her brush with little effort.

Andrea lives [near] Wales, and there are aspects of her work that link her to certain traditions – one might think of David Jones – and the remnants of ancient Celtic imagery that still continue today. She is following this thread, much of which still remains to be unravelled, and it is from these that she has woven her own poignant mythology. The slowness of her process contributes to this. These are not paintings that are carefully made over a matter of weeks or even months but of years, sometimes many years. Diaries that suggest both the passing of time and those things that remain constant.

There is something faintly reminiscent of the way that in Chinese and sometimes Japanese art, different views of landscapes, trees, bridges, rain and sunshine, are all miraculously knitted together on a two-dimensional surface. Impossible vistas presented together so convincingly that they seem more real than in life. As in dreams the heightened reality totally convinces, represents myriad objects and landscapes and perspectives simultaneously; this is what happens in Andrea’s work, except in her case it’s not just perspectives, but perspectives of time itself. Time passing and time frozen, time drawn from the past, from dreams, and from the future. There is an instinct here, raw as well as delicate, that reminds one that painting is still – in my view – a primal force that seemingly cannot be quite repressed by fashion or social movements. It reminds one also, that there were reasons for painting to have come into being. Not just for the useful hunting tasks they performed thirty thousand years ago as in cave paintings, but as something – possibly – even deeper. Something that through its expression can calm and justify the frantic human pain of existence, can point to a reason for its endurance, create catharsis.

And as there is no inconsistency in Andrea Mclean’s tiny, apparantly chaotic marks and images, it must be that the consistency with which they are presented – bound together – rests with two things: the obvious one her ability to formally contain and hold together all these disparate things; and the depth and stability and unchanging nature of that place from where they come.

Do we have a name for this place? No. Psyche is inadequate. Soul is somehow absurd. There is no name, but we know something about this place, nevertheless.

At the Slade I watched her paint the Bear for two years. It was one enormous canvas, a whirlwind with a polar bear caught at the centre.

There is no cynicism there, no conceptual affectation, but an explosive visionary exploration of an interior world that finds its expression through an enchanted view of the world she finds herself in. And over the two years this image moved and changed and was transformed and re transformed. The colours, in spite of being endlessly washed out and replaced, were always glowing. It seemed to become a moving image, shifting and tilting day after day, never satisfying her. And over all that time it somehow transferred itself to me, and, I would imagine, to the other students who worked with her.

Tess Jaray, Paintings: Mysteries and Confessions, Lenz Books

How does Andrea do it? Not by using traditional perspective, but by cradling her experiences and feelings, her memories and her dreams, in a particular kind of spatial structure, one you can find in medieval maps – which include past and present, fact and fiction, the universal and the minutest of details. The way she chooses to represent real places, her vision of them, as she says herself, is inspired by the medieval world, which she is drawn to through her love of medieval maps, of embroideries, of carvings and paintings. Her type of perspective is so flexible that it can merge two dimensions with three, and one in which the space glows with the beauty of color, thus producing a sense of the visionary, metaphysical in some ways, but rooted in experience. This is why you cannot apply the usual categories to her work, which is neither abstract nor representational, precisely because it is both.

In her recent paintings of the huge oak carving of the Jesse tree in Abergavenny, she represents what is now lost: the carved family tree that grew out of Jesse’s side; the tree as she imagines it. By revisiting the past, she brings it into the present. This is the painting of memory, which constantly sifts, reinterprets, and reinvents experience.

David Brancaleone, Exhibition Catalogue, Rochester Art Gallery